Jenkins on Kubernetes: From Zero to Hero

Using Helm and Terraform to host enterprise-grade Jenkins on Kubernetes.

Published September 30, 2020 --> Updated December 2, 2021

Quick Note: It's been over a year since I first posted this, and I imagine some details are now a little out of date. With that in mind, if you can stumble through any minor issues, I think you'll still learn a lot!

You can view this post on Medium here. If you run into issues here, it's probably because I missed something when converting the post to work here.

TL;DR

This post outlines a path to getting an enterprise-grade Jenkins instance up and running on Kubernetes. Helm and Terraform are used to make the process simple, robust, and easy to repeat.

A GitHub repo containing the code snippets from this post can be found here.

The Objective

With Kubernetes adoption growing like crazy, many organizations are making the shift and want to bring their favorite DevOps tool, Jenkins, along for the ride. There are a lot of tutorials out there that describe how to get Jenkins up and running on Kubernetes, but I’ve always felt that they didn’t explain why certain design decisions were made or take into account the tenants of a well-architected, cloud-native application (i.e. high availability, durable data storage, scalability). It’s pretty easy to get Jenkins up and running, but how do you set up your organization for success in the long run?

In this post, I will share a simplified version of a Kubernetes-based Jenkins deployment process that I have seen used at some of the top brands in the world. While walking you through the process, I will highlight each key design decision and give you recommendations on how to take the solution to the next level.

When evaluating a cloud architecture, I like to use the Well-Architected Framework from AWS to make sure I cover my bases. That framework focuses on operational excellence, reliability, security, performance efficiency, and cost optimization. For the purposes of brevity, we will just focus on a few key elements of reliability and operational excellence in this post, namely high availability, data durability, scalability, and management of configuration and infrastructure as code.

Helpful Prerequisites

To get the most out of this article, you should have a relatively good understanding of:

- Jenkins, how to use it, and why you would want to deploy it

- Kubernetes and how to deploy applications and services into a Kubernetes cluster

- Docker and containerization

- Unix shell (e.g. Bash) usage

- Infrastructure as code (IaC) principles

Technology Dependencies

To follow along and deploy Jenkins using the code samples in this post, make sure you have the following resources configured and on-hand:

- A Kubernetes cluster (tested on v1.16): this can be an AWS EKS cluster, a GKE cluster, a Minikube cluster, or any other functioning Kubernetes cluster. If you don’t have a cluster to work with, you can spin one up easily in AWS using the Terraform module enclosed here.

- Permissions to deploy workloads into your Kubernetes cluster, forward ports to those workloads, and execute commands on containers.

- A Unix-based system (tested on Ubuntu v18.04.4) to run command-line commands on.

- The kubectl command-line tool (tested on v1.18.3), configured to use your cluster permissions.

- Access within your cluster to download the Jenkins LTS Docker image (tested on Jenkins v2.235.3).

- The Helm command-line tool (tested on v3.2.4). Helm is the leading package manager for Kubernetes.

- The Terraform command-line tool (tested on v0.12.28). Terraform is a popular cross-platform infrastructure as code tool.

If you don’t have these dependencies ready to go, you can easily install and configure them using the links above.

Our Approach

This article will walk you through deploying Jenkins on Kubernetes with several different levels of sophistication, ultimately ending in our goal: an enterprise-grade Jenkins instance that is highly available, durable, highly scalable, and managed as code.

We will go through the following steps:

- Deploy a basic standalone Jenkins primary instance via a Kubernetes Deployment.

- Introduce the Jenkins Kubernetes plugin that gives us a way of scaling our Jenkins builds.

- Show what our basic setup is missing and why it is insufficient for our goals.

- Deploy Jenkins via its stable Helm chart (code for that chart can be found here), showing what this offers us and how it gets us close to the robustness we are looking for.

- Codify our Helm deployment using Terraform to get the many benefits of infrastructure as code.

- Go over additional improvements you can make to take Jenkins to the next level and highlight a few remaining key considerations to take into account.

Photo by Christopher Gower on Unsplash

Step One: Creating a Basic Jenkins Deployment

First things first, let’s deploy Jenkins on Kubernetes the way you might if you were deploying Jenkins in a traditional environment. Typically, if you are setting up Jenkins for an enterprise, you will likely:

- Spin up a VM to be used as the primary Jenkins instance.

- Install Jenkins on that instance, designating it as the Jenkins primary instance.

- Spin up executors to be used by the primary instance for executing builds.

- Connect Jenkins to your source control solution.

- Connect Jenkins to your SSO solution.

- Give teams access to Jenkins — most will not need UI access and can make due with webhook access maintained by a set of administrators— and empower them to run builds.

- Actively manage the system over time to make sure it is operating effectively.

Let’s walk through the first three steps, but do so in a “Kubernetic” way.

Pro tip: To run the examples in this post efficiently, I recommend opening up two shell instances. This will help when you go to port forward and want to run other commands at the same time.

First, let’s make sure our Kubernetes context is set up. If using AWS and EKS, this would mean running something like the following:

aws eks update-kubeconfig --region us-west-2 --name jenkins-on-kubernetes-clusterNext, let’s create a namespace to put all of our work in:

kubectl create namespace jenkinsFor simplicity, let’s change our Kubernetes context to look at the jenkins namespace we created above:

kubectl config set-context $(kubectl config current-context) --namespace jenkinsBecause we’ve done this, we won’t have to pass the --namespace argument to all of our future commands.

Now, we need to create several RBAC resources to enable our Jenkins primary instance to launch executors. To do this, save the following configuration to your file system as 1-basic-rbac.yaml:

apiVersion: v1

kind: ServiceAccount

metadata:

name: jenkins-service-account

namespace: jenkins

---

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

metadata:

name: jenkins-schedule-agents

namespace: jenkins

rules:

- apiGroups: [""]

resources:

["pods", "pods/exec", "pods/log", "persistentvolumeclaims", "events"]

verbs: ["get", "list", "watch"]

- apiGroups: [""]

resources: ["pods", "pods/exec", "persistentvolumeclaims"]

verbs: ["create", "delete", "deletecollection", "patch", "update"]

---

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: RoleBinding

metadata:

name: jenkins-schedule-agents

namespace: jenkins

roleRef:

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

kind: Role

name: jenkins-schedule-agents

subjects:

- kind: ServiceAccount

name: jenkins-service-account

namespace: jenkinsNavigate to the folder containing that configuration on your file system and run the following command:

kubectl apply -f 1-basic-rbac.yamlThis will create the RBAC resources we need in the cluster.

Now, save the following Deployment configuration to your file system as 2-basic-deployment.yaml:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

namespace: jenkins

name: jenkins-standalone-deployment

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app: jenkins

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: jenkins

spec:

containers:

- name: jenkins

image: jenkins/jenkins:lts

ports:

- containerPort: 8080

serviceAccountName: "jenkins-service-account"Navigate to the folder containing that configuration and run the following command:

kubectl apply -f 2-basic-deployment.yamlThis will create a Jenkins primary instance Deployment from the jenkins/jenkins:lts Docker image with a replica count of one. This Deployment will make sure that, assuming the cluster has enough resources, a Jenkins primary instance is always running in the cluster. If the Jenkins primary instance pod goes away for any reason other than Deployment deletion (e.g. crash, deletion, node failure), Kubernetes will schedule a new pod to the cluster.

Okay, wait for that Deployment to finish provisioning, checking every once in a while to see if the Deployment is in a Ready state using the kubectl get deployments command.

Once that Deployment is in a Ready state, we can forward a port to the container in our pod to see the Jenkins UI locally in our browser:

kubectl port-forward deployment/jenkins-standalone-deployment 3000:8080You should now be able to see the Jenkins Getting Started page in your browser at http://localhost:3000.

Pro tip: I highly recommend sticking to port 3000 if your setup allows you to. That should save you from some unexpected troubleshooting as you go through this post.

Alright. Because we have simply deployed the Jenkins base image and are not using Jenkins Configuration as Code, we have to configure the Jenkins primary instance manually.

On the first setup page, it asks you for your Jenkins administrator password. You can grab that password quickly by running the following:

kubectl exec -it deployment/jenkins-standalone-deployment -- cat /var/jenkins_home/secrets/initialAdminPasswordCopy that password, enter it into the password input field, and select continue.

On the next page, select Install suggested plugins and then wait for the plugin installation to complete.

Once the plugin installation completes, create a new administrator user with a name and password you will remember.

If this seems like a lot of work, and you are already convinced that this is not the best way to go about things, go ahead and jump to the section on Helm below.

Next, you can configure your Jenkins URL how you see fit. Its value is not important for this tutorial, but it is very important when you are actually using Jenkins in production. Go ahead and do that now, and then continue on until you have completed the initial setup wizard.

Hooray! If you followed the above steps, you now have a Jenkins primary instance running on Kubernetes and accessible in your browser. Of course, this is not how you would access your Jenkins UI in production — you would likely use an Ingress Controller or Load Balancer Service instead — but it is good enough for demonstration purposes.

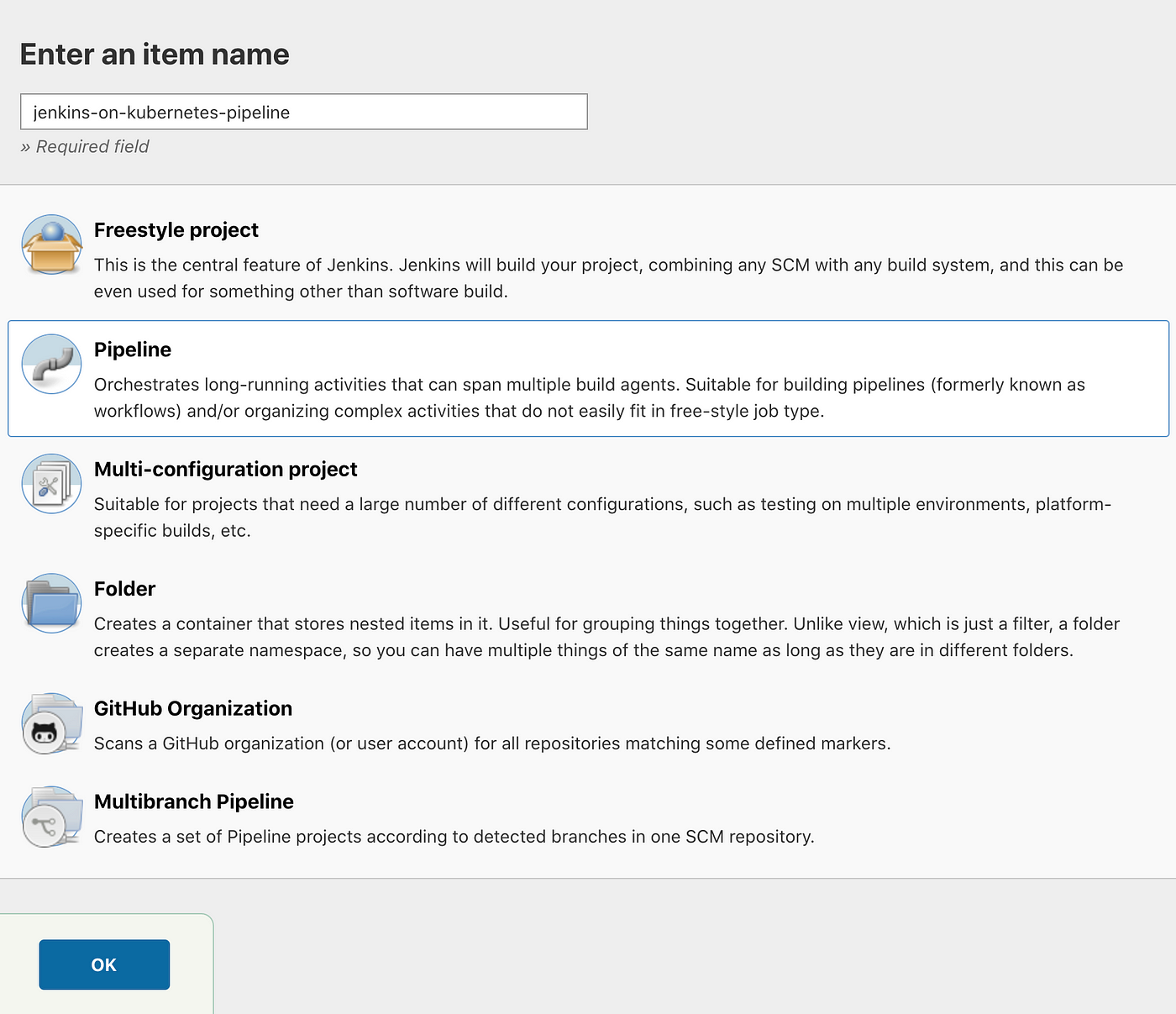

Okay, let’s create a simple Jenkins pipeline to make sure our Jenkins instance actually works. Go to http://localhost:3000/view/all/newJob or the equivalent URL based on your port forwarding setup and create a Pipeline with the name jenkins-on-kubernetes-pipeline— you may be prompted to enter your new admin user’s password. This will look like the following:

Now, go to http://localhost:3000/job/jenkins-on-kubernetes-pipeline/configure — you should be taken there automatically. In the box at the bottom of that page, paste the following simple pipeline code:

pipeline {

agent any

stages {

stage('Hello') {

steps {

echo 'Hello everyone! This is running inside your Kubernetes primary Jenkins instance container.'

}

}

}

}Now you can save your pipeline job and run a build by clicking Build Now.

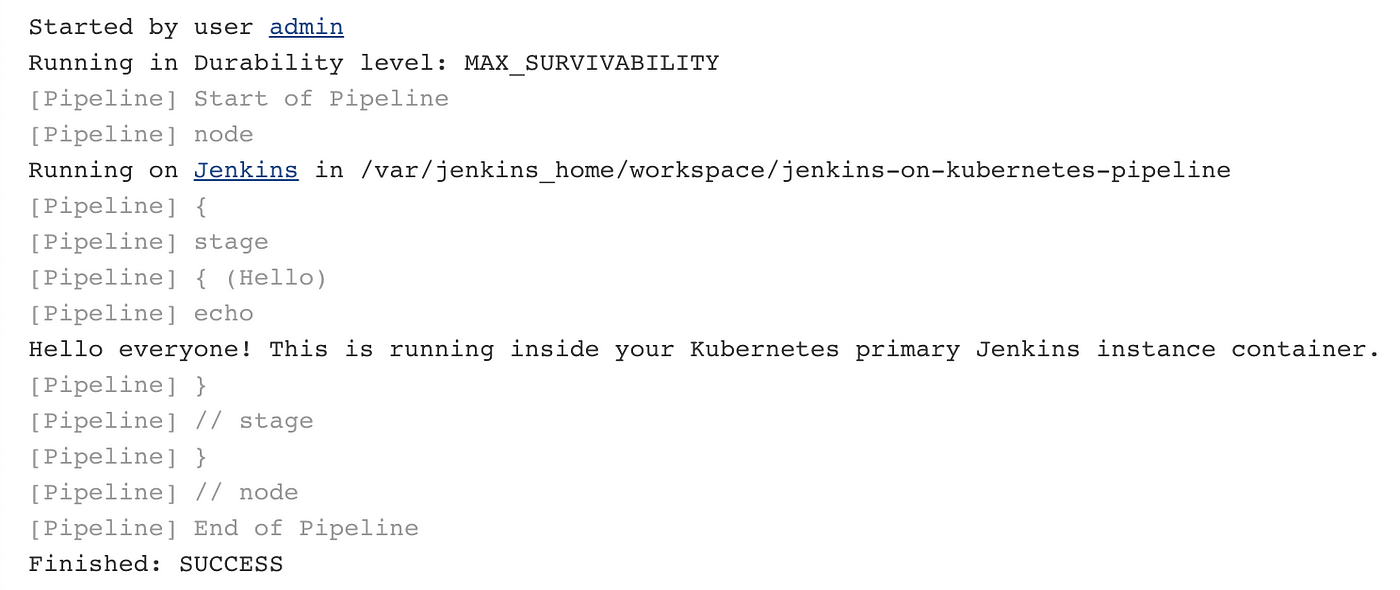

Wait a few seconds, and then you can view the console output here: http://localhost:3000/job/jenkins-on-kubernetes-pipeline/1/console. On this page, you will see the output from your pipeline. It should look approximately like this:

Terrific! We just ran a Jenkins build successfully on Kubernetes. Let’s move onto the next step.

Step Two: Introducing the Jenkins Kubernetes Plugin

The build that just ran successfully is awesome and all, but it ran on our Jenkins primary instance. This is not ideal because it limits our ability to scale the number of builds we run effectively and requires us to be very intentional about the way we run our builds (e.g. making sure to clean up the file system by clearing up workspaces).

If we stick with the current configuration, we will almost certainly run into trouble with space issues, unexpected file system manipulation side effects, and a growing backlog of queued builds.

So, how do we fix these issues seamlessly?

Enter the Jenkins Kubernetes plugin.

The Jenkins Kubernetes plugin is designed to automate the scaling of Jenkins executors (sometimes referred to as agents) in a Kubernetes cluster. The plugin creates a Kubernetes Pod for each executor at the start of each build and then terminates that Pod at the end of the build.

What this ultimately provides us with is scalability and a clean workspace for each build (i.e. better reliability and operational excellence). As long as you don’t exceed the resources available to you in your cluster — cluster autoscaling removes some of this concern — as many pods as you allow will be spun up to accommodate the builds in your queue.

Deploying Jenkins in this fashion also offers several additional benefits over a traditional VM deployment, including:

- Executors launch very quickly (i.e. better performance efficiency).

- Each new executor is identical to other executors of the same type (i.e. increased consistency across builds).

- Kubernetes service accounts can be used for authorization of executors in the cluster (i.e. more granular security).

- Executor templates can be made for different base images. This means you can run pipelines on different operating systems using the same Jenkins primary instance as the driver (i.e. improved operational excellence).

So, let’s get this set up.

First, we need to add a Kubernetes Service to Jenkins to allow it to be accessed via an internal domain name. To do so, save the following configuration to your file system as 4-basic-service.yaml:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: jenkins

namespace: jenkins

spec:

ports:

- port: 8080

name: primary

targetPort: 8080

- port: 50000

name: agent

targetPort: 50000

selector:

app: jenkins

type: ClusterIPNavigate to the folder containing that configuration and run the following command:

kubectl apply -f 4-basic-service.yamlNow we can configure the actual Kubernetes plugin.

Go to http://localhost:3000/pluginManager/available and search Kubernetes in the search box.

Select the box next to the plugin named Kubernetes and click Download now and install after restart at the bottom of the page.

Wait a few seconds for the plugin to download.

Now, go to http://localhost:3000/restart and click Yes. Wait a few minutes for Jenkins to restart. When it does, log back in with your admin credentials.

Pro tip: Jenkins restarts can be a little finicky. If your browser window does not reload after a minute or so, close that tab and open up a new one.

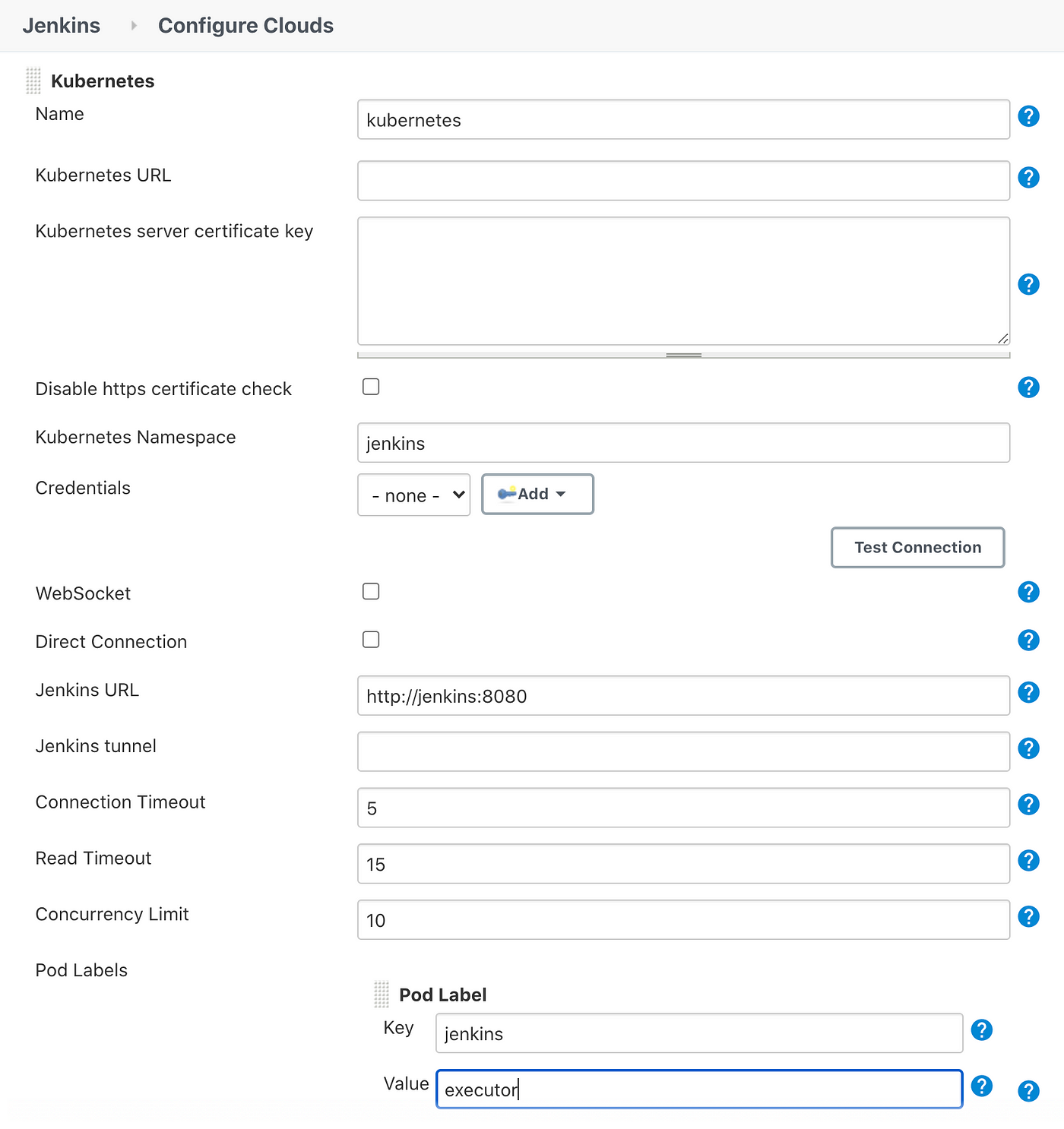

Once you are logged back in, go to http://localhost:3000/configureClouds/. This will look a little different on older versions of Jenkins.

On this page, add a Kubernetes cloud and then click Kubernetes Cloud details.

Configure the Kubernetes Namespace, Jenkins URL, and Pod Label like so:

Once you have that configured, click Save.

Now, let’s go modify our job (http://localhost:3000/job/jenkins-on-kubernetes-pipeline/configure) to use the new Kubernetes executors.

Change the contents of the pipeline to the following:

pipeline {

agent {

kubernetes {

defaultContainer 'jnlp'

}

}

stages {

stage('Hello') {

steps {

echo 'Hello everyone! This is now running on a Kubernetes executor!'

}

}

}

}Now, try running Build Now again.

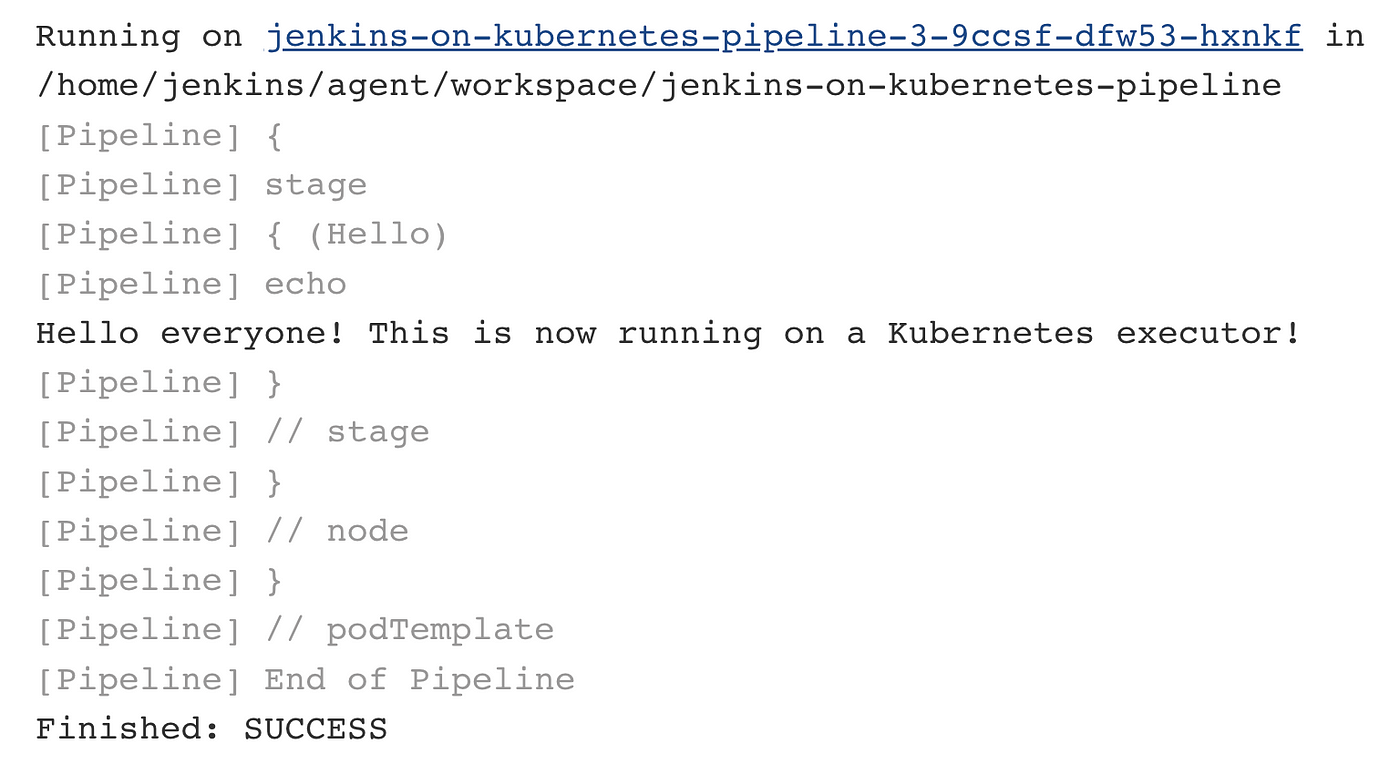

Wait a few seconds — it might even take a few minutes to launch the first executor — and then you can view the console output here: http://localhost:3000/job/jenkins-on-kubernetes-pipeline/2/console.

The output should look approximately like this:

Sweet! We now have a highly-available Jenkins primary instance, we can create jobs on that instance, we can run builds, and the number of Jenkins executor Pods will automatically scale as the build queue fills up.

We’re done, right?

Not so fast. Let’s keep going.

Step Three: Bringing the House Down

Though some might argue our setup is highly-available and scalable, what we just deployed is still not anywhere near the enterprise-grade solution we are looking for. To demonstrate that, let’s simulate a failure.

A common way to simulate failures on Kubernetes is to delete a Pod from a Controller (e.g. a Deployment or ReplicaSet). To do that, let’s first determine what Pods exist in our namespace:

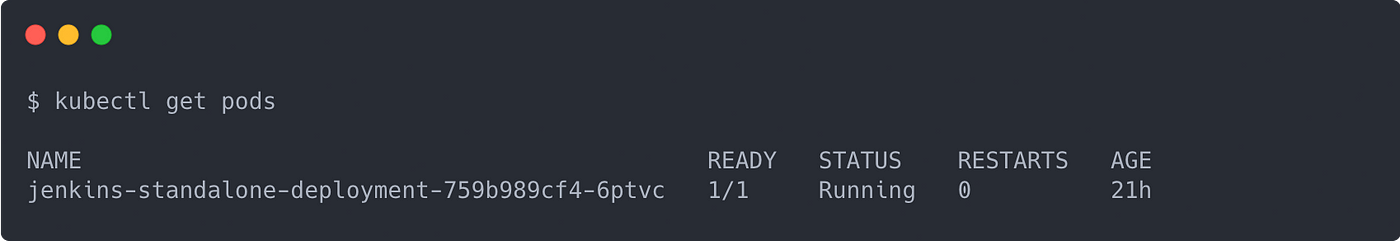

kubectl get podsYou should get something like this:

Now, you can delete that Pod like so:

kubectl delete pod jenkins-standalone-deployment-759b989cf4-6ptvcThis will kill your port forwarding session, so just expect that.

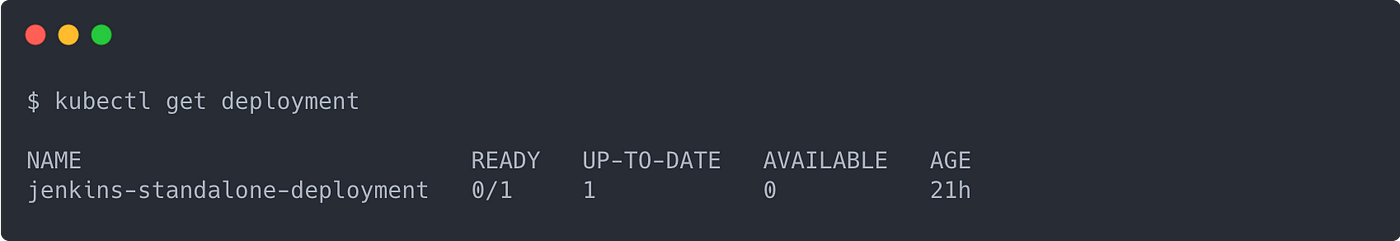

If you move quickly enough, you can then run kubectl get deployments and see a Ready state of 0/1 like the following:

Wait a few more seconds, though, and you will see something different. Your Deployment will eventually return to aReady state of 1/1. This means that Kubernetes noticed a missing Pod and created a new one to return the Deployment to the right number of replicas.

With our Deployment in a Ready state, we should be able to access the Jenkins UI again. Let’s confirm that by forwarding a port to the Deployment again:

kubectl port-forward deployment/jenkins-standalone-deployment 3000:8080Now, go back to http://localhost:3000 in your browser and refresh the page.

Uh oh…do you see what I see?

You should be seeing the Getting Started page again.

This is happening because we didn’t configure our Jenkins instance to have persistent storage. What we have deployed is roughly the equivalent of a Jenkins instance deployed on a VM with ephemeral storage. If that instance goes down, we go back to square one.

This is just one way in which our current setup is fragile. Not only is our Jenkins primary instance data not persistent, but this lack of persistence almost entirely nullifies the high availability benefits we get from using a Kubernetes Deployment in the first place. On top of that, our Jenkins configuration is largely manual and, therefore, hard to maintain.

Alright. Let’s fix this using our trusty friend, Helm.

Step Four: Deploying an Enterprise-Grade Jenkins With Helm

Helm is a package manager for Kubernetes. It operates off of configuration manifests called charts. A chart is a bit like a class in object-oriented programming. You instantiate a release of a chart by passing the chart values. These values are then used to populate a set of YAML template files defined as part of the chart. These populated template files, representing Kubernetes manifests, are then either applied to the cluster during a helm apply or printed to stdout during a helm template.

For our Jenkins installation, we will use the handy dandy stable helm chart. If you want to look at all of the values you can set for the version we use, take a look at the documentation on GitHub here.

To save some time, let’s keep most of the default values that come with the chart but pin the versions of the plugins we want to install. If you don’t do this step, you will likely run into issues with incompatible plugin versions as Jenkins and its plugins change over time.

Pro tip: If you are working with a chart and want a values.yaml file to work off of, repos usually come with one that holds all of the default values for the chart.

By default, out of the box, this helm chart provides us with:

- A Jenkins primary instance Deployment with a replica count of one and defined resource requests. These resource requests give Jenkins priority over other Deployments without resource requests in the case of cluster resource limitation.

- A PersistentVolumeClaim to attach to the primary Deployment and make Jenkins persistent. If the Jenkins primary instance goes down, the volume holding its data will persist and attach to the new instance that Kubernetes schedules in the cluster.

- RBAC entities (e.g. ServiceAccounts, Roles, and RoleBindings) to give the primary instance Deployment the permissions it needs to launch executors.

- A Configmap containing a Jenkins Configuration as Code (JCasC) definition for setting up the Kubernetes cloud configuration and anything else you want to configure — to change this configuration, you would modify the

valuesfile you pass into the Helm chart. - Configmap auto-reloading functionality through a Kubernetes sidecar that makes it so JCasC can be applied automatically by updating the JCasC Configmap.

- A Configmap for installing additional plugins and running other miscellaneous scripts.

- A Secret to hold the default admin password.

- A Service for the Jenkins primary instance Deployment that exposes ports 8080 and 50000. This makes it easy to connect Jenkins to an Ingress Controller, but also allows the Jenkins executors to talk back to the primary instance via an internal domain name.

- A Service to access the executors with.

Sounds a lot more robust than what we just built ourselves, doesn’t it? I agree! Let’s get that up and running in our cluster.

Before we do, let’s clean up our previous work by running the following:

kubectl delete -f 1-basic-rbac.yaml

kubectl delete -f 2-basic-deployment.yaml

kubectl delete -f 4-basic-service.yamlNow, let’s set up a values file to pass into the Helm chart. To do so, save the following to a file named 6-helm-values.yaml:

master:

installPlugins:

- ace-editor:1.1

- apache-httpcomponents-client-4-api:4.5.10-2.0

- authentication-tokens:1.4

- bouncycastle-api:2.18

- branch-api:2.5.8

- cloudbees-folder:6.14

- command-launcher:1.4

- configuration-as-code:1.42

- credentials:2.3.12

- credentials-binding:1.23

- display-url-api:2.3.3

- durable-task:1.34

- git:4.3.0

- git-client:3.3.1

- git-server:1.9

- handlebars:1.1.1

- jackson2-api:2.11.1

- jdk-tool:1.4

- jquery-detached:1.2.1

- jsch:0.1.55.2

- junit:1.29

- kubernetes:1.26.4

- kubernetes-client-api:4.9.2-2

- kubernetes-credentials:0.7.0

- lockable-resources:2.8

- mailer:1.32

- matrix-project:1.17

- momentjs:1.1.1

- pipeline-build-step:2.12

- pipeline-graph-analysis:1.10

- pipeline-input-step:2.11

- pipeline-milestone-step:1.3.1

- pipeline-model-api:1.7.1

- pipeline-model-definition:1.7.1

- pipeline-model-extensions:1.7.1

- pipeline-rest-api:2.13

- pipeline-stage-step:2.5

- pipeline-stage-tags-metadata:1.7.1

- pipeline-stage-view:2.13

- plain-credentials:1.7

- scm-api:2.6.3

- script-security:1.74

- snakeyaml-api:1.26.4

- ssh-credentials:1.18.1

- structs:1.20

- trilead-api:1.0.8

- variant:1.3

- workflow-aggregator:2.6

- workflow-api:2.40

- workflow-basic-steps:2.20

- workflow-cps:2.81

- workflow-cps-global-lib:2.17

- workflow-durable-task-step:2.35

- workflow-job:2.39

- workflow-multibranch:2.21

- workflow-scm-step:2.11

- workflow-step-api:2.22

- workflow-support:3.5Now we are good to deploy Jenkins using Helm. To do so, the process is super simple. Run:

helm repo add stable https://kubernetes-charts.storage.googleapis.com/and

helm install jenkins stable/jenkins --version 2.0.1 -f 6-helm-values.yamlPro tip: It is almost always helpful to pin a version to entities like a Helm chart, a library, or a Docker image. Doing so will help you avoid a drifting configuration.

This will create a Helm release named jenkins that contains all of the aforementioned default features. Give that some time, as it does take a while to get Jenkins up and running.

It is important to note that there are a lot of extra features (e.g. built-in backup functionality) that we don’t take advantage of here with the default chart configuration. This is meant to be a starting point for you to build on and explore. I highly recommend evaluating the chart, creating your own version of the chart, and customizing it to meet your needs before deploying it into a production environment.

Once you have given the release time to deploy, run helm list to verify it exists.

To get the admin password for your Jenkins instance, run:

printf $(kubectl get secret --namespace jenkins jenkins -o jsonpath="{.data.jenkins-admin-password}" | base64 --decode);echoThis is a little different from the last command we ran to fetch the password because the password is now stored as a Kubernetes Secret.

Then, run the following to forward a port:

export POD_NAME=$(kubectl get pods --namespace jenkins -l "app.kubernetes.io/component=jenkins-master" -l "app.kubernetes.io/instance=jenkins" -o jsonpath="{.items[0].metadata.name}")

kubectl --namespace jenkins port-forward $POD_NAME 3000:8080Now you will be able to see Jenkins up and running at http://localhost:3000 again.

Now, let’s test our release and make sure we can run builds.

Once again, go to http://localhost:3000/view/all/newJob and create a Pipeline with the following code:

pipeline {

agent {

kubernetes {

defaultContainer 'jnlp'

}

}

stages {

stage('Hello') {

steps {

echo 'Hello everyone! This is now running on a Kubernetes executor!'

}

}

}

}Pro tip: You could also use the Helm chart to add jobs on launch or the Job DSL plugin to add jobs programmatically. I would recommend the latter in a production environment.

Click Build Now again, and let’s marvel at what Helm just did for us.

Hopefully, your build ran successfully. If it did, awesome! Let’s make this setup even better.

Step Five: Moving Our Deployment to Terraform

In the current state, we have checked most of the boxes that we were looking for in an enterprise-grade Jenkins deployment, but we can improve our setup even more by managing it with infrastructure as code.

Terraform is the infrastructure as code solution I see used most in industry, so let’s use it here.

Essentially what Terraform does is take a configuration, written in HCL, convert that configuration into API calls based on a provider, and then make those API calls on your behalf with the credentials made available to the command-line interface. Because we are already authenticated into the cluster, and we are the ones calling Terraform commands, Terraform will be able to deploy the Jenkins Helm chart.

First, let’s delete our existing helm release: helm delete jenkins. Verify the release no longer exists with helm list.

Now, save the following Terraform configuration to a file called 7-terraform-config.tf:

resource "helm_release" "jenkins" {

name = "jenkins"

repository = "https://kubernetes-charts.storage.googleapis.com"

chart = "jenkins"

version = "2.0.1"

namespace = "jenkins"

timeout = 600

values = [

"${file("6-helm-values.yaml")}"

]

}Awesome, now we can use Terraform to deploy our chart.

Run terraform init in the directory where you put 7-terraform-config.tf. This will initialize a state file that holds Terraform state — typically you would store this state remotely using something like Amazon S3.

Now, run terraform plan. This will print out what is going to change in the cluster based on the configuration you have defined. You should see that Terraform wants to create a helm release named jenkins.

If this looks good to you, run terraform apply. This will give you one more chance to make sure you want to apply your changes. If everything seems to check out, which it should, reply yes when Terraform asks for validation input.

After a few minutes, you should have an enterprise-grade Jenkins up and running again! Booyah!

Pro tip: Terraform is great for a lot of things, but one of my favorite things it provides is drift detection. If someone goes and changes this helm chart ad-hoc, you will be able to tell by running a terraform plan and checking to see if any changes show up in the plan.

We’re almost done here, but I would be remised if I didn’t go over a few additional recommended improvements and considerations with you. Check those out below.

Step Six: Improvements and Considerations

Now that you have an enterprise-grade Jenkins up and running, you probably want to make it more useful to your organization by making the following improvements:

- Set up SSO via a plugin like OpenId Connect Authentication or OpenID.

- Open up your firewall to allow communication with your source control solution.

- Create a custom executor image and custom pod template to be used for builds. This will allow you to install common dependencies across builds and will decrease build time.

- Create a set of Jenkins Shared Libraries for teams in your organization to call upon when running deployments. Using these, you can define guardrails for what teams can and cannot do with their Jenkins usage. In fact, with this, you can set it up so very few people actually need access to the UI, and developers can just run builds by pushing to source control.

- Convert the stable Helm chart we used above to a custom one stored in source control. This will allow you to manage changes to the chart over time and make sure you have more control over its lifecycle.

- Set up monitoring via Prometheus and Grafana to evaluate the health of your Jenkins instance over time.

- When deploying applications and services, configure Jenkins jobs to perform zero-downtime and blue-green deployments. This link will help you do that.

- Add theming to make Jenkins a little cleaner by using something like the Simple Theme plugin.

I also recommend you take the following considerations into account:

- If you want to stick with block storage for storing data from the primary Jenkins instance, you will want to add an automated volume backup system to restore from if the volume is ever corrupted. Using a tool like Velero simplifies the backup process, and you can actually use it to back up and restore your entire cluster in the event of a disaster.

- If you want a more dynamic storage option and are using EKS, you might want to set up something like the EFS Provisioner for EKS to back Jenkins with a scalable file system.

- If you want to deploy non-Helm workloads to Kubernetes using Terraform, take a look at the alpha provider for Kubernetes. It allows you to deploy any Kubernetes configuration that you can deploy without Terraform, something the original Kubernetes provider could not do. More information on your options for this workflow can be found here.

- Regularly check to make sure your Jenkins plugins are up-to-date. In general, I recommend limiting the number of plugins you install as much as possible. From a security perspective, plugins are one of the weakest links for Jenkins, so limit their use and keep them up to date.

- Finally, empower your developers to dive in and build great stuff!

Conclusion

If you’ve made it this far, fantastic! I hope that this post was valuable to you and you learned something new. You rock!

A GitHub repo containing the code snippets from this post can be found here. If you find it helpful, go ahead and give it a star. If you run into any issues, please submit a pull request to that repo, and I will do my best to respond.

Take care!

Addendum

Throughout this post, the commonly-used terms master and slave are substituted with primary and executor to be more inclusive.